The New York Times recently published an article about hats and hat shops in New York. Reading the article, you will find both the hip hop influence (pink homburg) as well as the classic fedora influence ("we can do better"). The two, while still very much at odds, are bringing about another resurgence of the fedora much like that found after the "Raiders of the Lost Ark" though today's comeback seems to be staying longer over numerous demographics and involves more people, both male and female. Frankly, I am very wary of the hip hop culture but for once I think it is doing something good even if the fedoras it sells are cheap and, in my personal view, ugly beyond belief. One day (we hope) those kids and young adults will acquire grown up tastes and will find something better than the Wal-Mart fedoras.

Here's the article.

----------------------

From Harlem to Midtown for That Item to Top Off a Look

By HARRY HURT III

Published: September 22, 2007

I TAXIED up to Harlem in executive pursuit of a stylish lid with my buddy Michael Holman. The morning was cool because a rain front had blown through the night before. Litter swirled around like fall leaves on the wide concrete sidewalks. Holman, balding and bareheaded, was styling Malcolm X glasses, a green leather jacket and a two-day growth of beard.

“It all starts at the top,” he said, staring out the window and grinning.

The cab dropped us off at 146th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, a k a Seventh Avenue, next to a narrow storefront called Harlem’s Heaven. Holman groaned. The wares in the window were ornate, what he called “Sunday-go-to-meeting hats for ladies.” I knocked anyway, and a saleswoman named Danielle, with dreadlocks and a flashing smile, let us in.

“We do have some men’s hats,” Danielle said. “They’re in the back.”

That seemingly innocent remark set the tone for the rest of our quest. Before World War II, hats were an essential part of a man’s wardrobe. Look at photographs of Wall Street crowds in the 1920s and 1930s and you’ll see virtually every male wearing some type of hat, even if he was about to lose his shirt. In recent decades, however, men’s hats, other than baseball caps, have been all but forgotten in fashion.

From August 2006 to July 2007, sales of men’s headwear in the United States were slightly over $1.1 billion, according to the NPD Group, a market research firm. But more than 75 percent of those sales were caps as opposed to fedoras, homburgs and the like. By comparison, sales of women’s headwear, slightly over $1.2 billion, were split roughly 47 percent to 53 percent between caps and hats.

There are almost as many theories about the demise of men’s hats as there are full sizes and quarter sizes. Some hatters say that veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict were weary of military uniformity and shunned hats when they returned to civilian life. Some blame President John F. Kennedy, who wore a top hat to his inauguration but delivered his Inaugural Address bareheaded. Others cite automobiles, whose roofs made hats uncomfortable and unnecessary. My buddy Holman pinned it on the anti-establishment sentiment of the 1960s.

“Men’s hats symbolized the conformity of the 1950s, and the nonconformism of the 60s was a reaction against all that,” he observed as we browsed the back room at Harlem’s Heaven. “You also had men growing their hair long, and hats didn’t fit well with that. When you took off your hat, you got this rumpled ring around your head called ‘hat hair.’ ”

At 48, Holman exudes the kind of hipness I couldn’t affect in my wildest dreams. A filmmaker who teaches at Howard University in Washington, he is also a writer, a musician and a sartorial trendsetter. In 1979, he formed a rock band called Gray with the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat; later, he was a co-author of a screenplay about Basquiate, filmed by Miramax. When performing on stage, Holman and his bandmates wore gray sharkskin suits and porkpie hats.

Despite statistical evidence to the contrary, Holman insists that men’s hats are coming back in style. I trusted his cultural judgment on its own merits and because we share an ancestral connection to Texas. His great-great-great-grandfather, William Holman, fought in the Texas war for independence from Mexico in 1836. A street in Houston, my hometown, is named for William Holman. “You and I are brothers from another mother,” Michael Holman joked.

Not surprisingly, the selection of men’s hats at Harlem’s Heaven was pretty slim. I tried on a wide-brimmed black homburg called the Godfather after the hat Al Pacino wore in the movie. Danielle said it made my face look fat. Holman recommended a blue fedora with a narrower brim. I liked it, too, but it was a Habig, imported from Vienna, and it cost $199, which was quite a bit more than I had planned to spend.

Holman insisted that we check out a store called Porta Bella on 125th Street a few doors down from the Apollo Theater. Its walls were decked with yellow, red and powder-blue zoot suits priced as low as $119. The equally colorful if rather meager stock of men’s hats was stashed in plastic bags in the back of the store. At Holman’s urging, I tried on a $10 pink fedora.

“Oh, man, that’s dope!” he exclaimed.

“Is that good?” I asked.

“Oh, yeah,” Holman replied. “You’ve got to have that hat.”

Immediately upon striding back out onto 125th Street, I began to have second thoughts about the pink homburg. A tall, muscular fellow with a New York Yankees cap looked back over his shoulder at me and shook his head and chortled like I was some kind of circus clown. A woman in ragged clothes begged me to give her a dollar.

“This hat may be dope, but I feel like one,” I told Holman as we hailed another cab.

We taxied down to Worth & Worth at 45 West 57th Street. The firm, established in 1922, has provided hats for clients like William S. Burroughs and David Bowie. We were greeted in the sixth-floor showroom by the resident designer Orlando Palacios, 43, who was wearing a sleeveless shirt and a Stetson festooned with a black stenciled badge that read “Sex Pistols.” Like Holman, Orlando said that men’s hats were making a comeback.

“People want to step away from that cookie-cutter image,” he said. “A hat will change your whole look. It says you’re daring. It pulls people in.”

In addition to Stetsons, Worth & Worth features classic fedoras and homburgs with names like Fellini and Venezia. Orlando also makes custom hats, starting at $450. Holman fancied a vintage-style Donegal tweed cap known as an Applejack or a newsboy, priced at $65. I bought it for him in thanks for his shopping assistance, complimenting him with one of the few hipster terms in my vocabulary.

“You look fly,” I said.

Orlando suggested that I try on a butterscotch Prima Vera fedora made of rabbit and beaver fur. I appreciated the quality of the hand stitching but balked at the $375 price. “That hat’s just got way too much drama,” Holman whispered when Orlando was out of earshot. “And the brim is too wide for your face.”

A few minutes later, Holman and I arrived at Arnold Hatters at 535 Eighth Avenue. The proprietor, Arnold Rubin, 72, welcomed me with a knowing wink. The last time I had visited his store, I was about to have surgery to correct a hammertoe. With Arnold’s guidance, I picked out a chestnut cane to use after the operation as I recovered. This time, I donned my new pink homburg just to see how he would react.

“Looks like you’re walking pretty good,” Arnold said. “We can do better hat-wise.”

Arnold Hatters boasts an inventory of over 160 styles, some of them in as many as 24 colors. Among its celebrity customers are the actor Jimmy Smits, the rapper Ice T and the singer Janet Jackson, who bought a hat the previous Saturday. Arnold fitted me with a $120 navy blue felt fedora with a relatively narrow 2-inch brim, by Bailey of Hollywood.

I reached into the pocket of my blazer and pulled out a 3 1/2-inch steel pin tipped with a pearly white bulb. Arnold helped me stick it into the grosgrain band of the fedora. He asked where on earth I had found such an elegant hatpin. I told him the surgeon had inserted it into my foot to repair the hammertoe. Holman whistled softly.

“Now that is really dope,” he said.

link

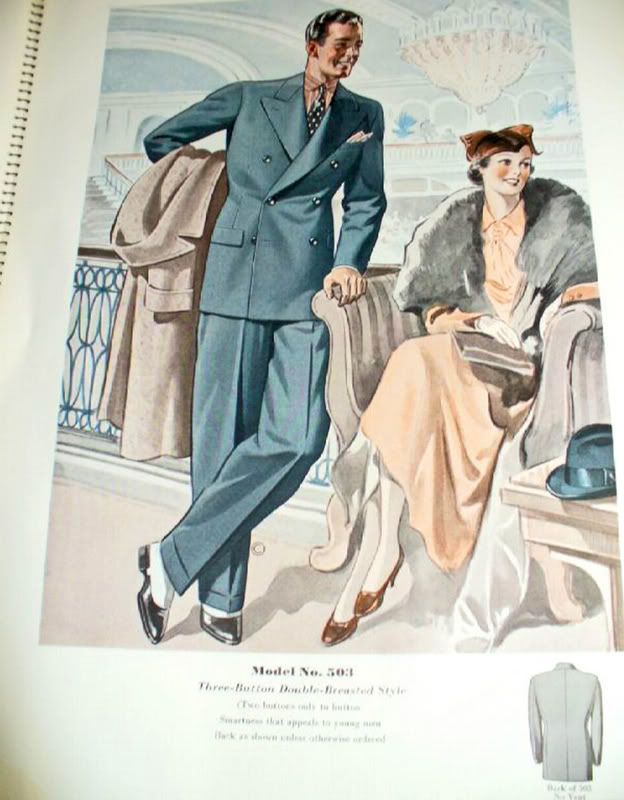

One thing you might notice in the above photo is that the vintage trou is missing cuffs while the modern George trousers have cuffs. While cuffs were prevalent during the Golden Age they were not always present as a result of fads, personal preferences and even the need to let them down to lengthen the trou to accomidate longer legs.

One thing you might notice in the above photo is that the vintage trou is missing cuffs while the modern George trousers have cuffs. While cuffs were prevalent during the Golden Age they were not always present as a result of fads, personal preferences and even the need to let them down to lengthen the trou to accomidate longer legs.

-Modern 100% wool suit

-Modern 100% wool suit

"1970s" you ask? Yes, the early 1970s had some very nice vintage inspired clothing, as the above jacket can attest to. The mid-1970s harkened in the attrocities we so commonly see hanging ownerless in thrift stores.

"1970s" you ask? Yes, the early 1970s had some very nice vintage inspired clothing, as the above jacket can attest to. The mid-1970s harkened in the attrocities we so commonly see hanging ownerless in thrift stores.

But the patterns and scenes were not the only points where vintage ties blow away modern ties. The fabrics used were incredible, most ties being made of incredibly smooth, soft and flexible silk, though many were made of cotton and even wool, as seen in the tie below.

But the patterns and scenes were not the only points where vintage ties blow away modern ties. The fabrics used were incredible, most ties being made of incredibly smooth, soft and flexible silk, though many were made of cotton and even wool, as seen in the tie below.

Billy

Billy