http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2007/08/talese200708The Scion, the Stitch, and the Wardrobe

Custom-tailored suits, with their carefully sculptured contours and other personalized details, have become a rarity over the last half-century. The author, a noted clotheshorse who was named to this year's International Best-Dressed List, bemoans the decline of this intimate craft, which was mastered by several generations of his male ancestors, including his father.

By Gay Talese

August 27, 2007

There are people who are greatly concerned about the environment and the well-being of Bengal tigers and yellow-headed Amazon parrots. And then there are people like me who worry about the professional survival of men's custom tailors. Each year I spend large sums of money in shops that employ these craftsmen, whom I see as an endangered species.

I have personally witnessed the economic decline and diminution of tailors, because my late father was one of them. An "artist with a needle and thread" is how I remember him. His occupational pride was rarely enriched by a sufficient number of customers to make his endeavors worthwhile, and thus most of our family's income during my Jersey-shore boyhood was derived from a flourishing dress boutique founded by my sociable and commercially minded mother. Still, I have fond recollections of my father's shop as it existed half a century ago: the bolts of exquisite fabric on the counters; the dressing rooms with red velvet curtains and three-sided mirrors; the framed posters of elegantly attired men wearing homburgs and fedoras, suits with pocket handkerchiefs, and overcoats with boutonniered buttonholes. Some of the men in the posters carried walking sticks; they were boulevardiers strolling through the streets of Paris, a city my father first came to know in 1920 during his stay as a 17-year-old apprentice eager to refine the tailoring skills he had begun learning after school in an uncle's shop in his native Italy.

My father made most of my suits during my school years through college. There had been tailors in his background for five generations, beginning in the early 1800s. His ancestors (and mine) dwelled in hillside villages and towns in the rugged mountains of Southern Italy, where there existed, especially among bride-seeking bachelors, a desire to wear fine clothes and create a favorable impression on young ladies. In the early evenings, these traditionally shy women stood watching within the shadows of residential balconies overlooking the main square, where crowds of men gathered to smoke and converse among themselves and sometimes walk around in pairs, arm in arm, in what was both a courtship ritual and an exhibition of masculine fashion.

In this early-20th-century setting, known as the passeggiata, the local tailors competed with one another to showcase their sartorial talents. Collectively they refined a particular style of dress in accord with the inherent vanity of Italian men, many of whom lived in quite modest circumstances. Indeed, in this part of Italy, where poverty was prevalent, there was an overwhelming interest in appearances; dressing up was a strategy for elevating one's public image. Making a good impression—fare la bella figura—was inbred in the culture, and engaging the services of a talented tailor was one of the simplest ways to get noticed. This may explain why so many of the outstanding tailors in Europe and the United States were either born in Southern Italy or influenced by the region's individualistic and rather rakish mode of male attire. While the English tailors of Savile Row produced clothing that bespoke an understated elegance, there was nothing understated about the work of the Italians: it suggested a demonstrative spirit, an emboldened nature, a desire to elicit the attention of young women on balconies. Most prominently, the Italian style was characterized by embroidered buttonholes and decorative stitching or piping along the edges of the lapels and down the outer seams of the trousers. In contrast to the slope-shouldered suits produced by the English, the Italians favored broad, slightly raised shoulders as well as colorful silk linings that could be glimpsed through the double vents at the back of the jackets.

It was in Paris that I developed a sophisticated appreciation of the tailor's art. During a trip there in the mid-1950s, on furlough from a U.S. military base in Germany, I visited an older cousin of my father's named Antonio Cristiani, who had left Italy for France in 1911 and operated a very successful shop near the Paris opera house on the Rue de la Paix. From that first tour of Cristiani's showroom I became a devotee of his suits, and in the ensuing years, as I gradually earned enough money from my writing to afford being a customer, I was fitted for dozens of them, each one costing between $2,500 and $3,000—even with my family discount. But I've always been able to justify this spending, as I alluded to earlier, because I see myself as helping to underwrite the continued existence of an endangered species of craftsmen who produce handstitched apparel. Whenever I purchase yet another suit, I remind myself that the money I'm spending would buy another man a new set of golf clubs. (I don't play golf.) Moreover, my entire wardrobe—between 80 and 90 suits from such distinguished names as Brioni, Zegna, Smalto, DiMitri, Battaglia, and Meledandri, as well as Cristiani—would hardly match the purchase price of any one of the 40-foot motor yachts I see in such abundance whenever I cross a bridge near my summer home in Ocean City, New Jersey.

Yet it seems impertinent to make financial comparisons when what I'm mainly interested in is the aesthetics of the tailoring profession, and my small part within it as a patron, a preservationist, and an advocate of the perfect fit—and the idea that measurements can alter the mind. A large percentage of the suits I wear are 20, 30, even 40 years old, and they are mostly representative of the classic 1930s style, my favorite period. But they are never out of fashion, since these clothes set their own fashion. There are double-breasted and single-breasted suits—both with waistcoats in some cases—and they have high pointed lapels or rounded lapels of a unique cut that sets them apart. They are dateless in a sense and, because they are carefully crafted, are long-lasting. If something I like is damaged or beyond repair—such as a Paris-made Smalto jacket stained by my ink pen—I have the jacket copied by a tailor I know in New York, and thus it lives on in thread and fabric. Since I like holding on to my clothes, however, it is important that I not gain weight. I have kept my weight at pretty much the same for nearly a half-century, meaning I work out a lot and try to stay away from ice cream.

Putting on a beautifully designed suit elevates my spirit, extols my sense of self, and helps define me as a man to whom details matter. Well-tailored clothing is a celebration of precision. When I'm wearing one of my custom suits, I'm in harmony with my highest ideals, my worship of great workmanship. In this period of globalization and outsourcing, of voicemail vacuousness and shopping on the Internet, there are few things more gratifying to me than standing in a clothing shop getting a second or third fitting from a tailor who is personally and pridefully engaged in what he's doing.

Gay Talese is the author of 11 books, including The Kingdom and the Power, Thy Neighbor's Wife, Unto the Sons, and, most recently, A Writer's Life. His Web site resides at

gaytalese.com.

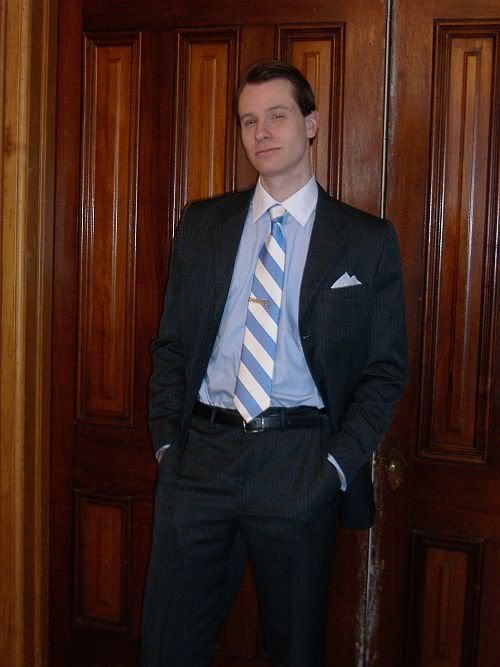

Unattractive and not very useful at all. Uncomfortable, infact.

Unattractive and not very useful at all. Uncomfortable, infact. Vintage suits nearly always had high armholes. High armholes are cut higher under the armpit and don't deform the jacket when the arms rise. Truly high armholes might be a tad uncomfortable (tight under the armpits) at first for anyone who normally wears jackets with low armholes but they are amazed when they lift their arms and the jacket stays in place.

Vintage suits nearly always had high armholes. High armholes are cut higher under the armpit and don't deform the jacket when the arms rise. Truly high armholes might be a tad uncomfortable (tight under the armpits) at first for anyone who normally wears jackets with low armholes but they are amazed when they lift their arms and the jacket stays in place.

Yep, low armholes. FAIL!

Yep, low armholes. FAIL!

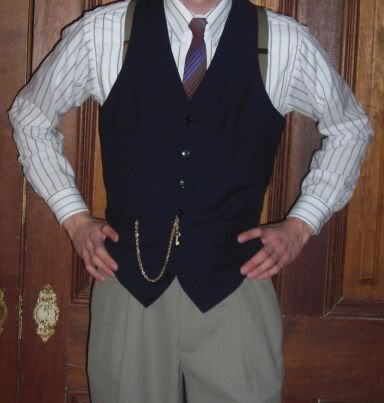

I must say, I love that 6x3 jacket. It fits me so well and the lazy peaked lapels are so early 20th century in design.

I must say, I love that 6x3 jacket. It fits me so well and the lazy peaked lapels are so early 20th century in design.

If you have ever found something of great value then you know what it was like for me finding this hat.

If you have ever found something of great value then you know what it was like for me finding this hat.